Aug 19, 2016 - Water Determines Territorial Boundaries By Dakota Wind

Hunkpapa and Yanktonai Homeland Traditional Territory Defined by Water

Cannonball, ND – In 1915, Colonel Welch met Wakíŋyaŋ Tȟó (Blue Thunder), a renowned camp crier (his voice was said to have carried five miles) and traditional historian of the Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna Dakȟóta and Húŋkpapȟa Lakȟóta at Fort Yates, ND. Welch asked Blue Thunder from where he came. Blue Thunder replied that he was born on Tȟaspáŋna Wakpána (“Thorn Apple Creek;” Apple Creek), or Bismarck, ND.

Blue Thunder’s answer reflected the pre-reservation tradition of naming the stream along which one was born, from which one came, by way of introductions. It also enforced the ideology of territorial boundary. The post reservation Dakȟóta or Lakȟóta named the tribe (or campfire)/band one belonged to, or whose parents belonged to, in introduction. Today, a Dakȟóta or Lakȟóta is likely to name his or her agency where he or she is enrolled at, in introduction.

In 1796, John Evans established Jupiter’s Fort, on the north bank of the Cannonball River. The Blue Thunder Winter Count and the No Two Horns Winter Count recall Evan’s arrival with an image of the British Union Jack and the accompanying entry: Wówapi waŋ makȟá kawíŋȟ hiyáyapi (Flag/book a earth to-turn-around came-and-passed-along-they), or” They brought a flag around the country.”

Evans chose the location for his trading post with an eye towards finding a safe middle ground amongst the Šahíyela (Cheyenne), the Mawátani (Mandan) and Ȟewáktokta (Hidatsa), the Phadáni (Arikara), the Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna, and the Húŋkpapȟa. That middle ground was near the confluence of the Íŋyaŋwakaǧapi Wakpá (Stone Production River; Cannonball River) and Mníšoše (The Water Astir). This site was generally held to be sacred by all the regional tribes.

The Nu’Eta (“The People,” as the Mandan refer to themselves) regard the twin buttes there on the south bank of Íŋyaŋwakaǧapi Wakpá with reverence, and is tied to their flood story. An old Mandan village is located in close vicinity of Jupiter’s Fort. The Sahnish (as the Arikara call themselves) lived there too for a time before moving to Míla Wakpá (Knife River; present day Stanton, ND). An ancient declaration inspired the Sahnish to ascend the Mníšoše, and they did, breaking away from their Caddo relatives a thousand years ago, then breaking away from their Pawnee relatives in the past three hundred.

A look across to the east bank of the Missouri River, the ancient homelands of the Arikara and the Yanktonai Dakota.

Where the Íŋyaŋwakaǧapi Wakpá converges with the Mníšoše, the hydrographical energy of the two resulted in a great swirl in the river. From this whorl of water was shaped the cannonball stones of various sizes. According to Jon Eagle Sr, Tribal Historic Preservation Officer at Standing Rock, since the creation of Lake Oáhe (Something To Stand On), the whorl no longer labors to fashion the round stones.

In 1763, according to the Brown Hat Winter Count, in the vicinity of the Íŋyaŋwakaǧapi Wakpá, there came an Oglála war party to fight the Šahíyela who lived nearby. The war party fought their fight and returned to the east bank of the Mníšoše. The Šahíyela retaliated by crossing the Mníšoše and setting the plains afire. The wind carried the fire directly to the Oglála camp, causing a great run for Blé Haŋská (Long Lake). The fire caught up to them before the survivors jumped into the lake, burning many. The survivors were thereafter called Sičáŋǧu (Burnt Thighs).

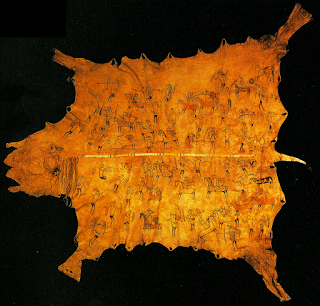

A painted bison robe depicting a conflict between the Arikara, Hidatsa, Mandan, Hunkpapa, and Yanktonai in 1798.

In 1798, according to the Pictographic Bison Robe (of Mandan manufacture, gifted to the Corps of Discovery in 1804) the Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna and Húŋkpapȟa went to war against the Phadáni, Ȟewáktokta, and Mawátani. The war, one of many intertribal conflicts across the years, concluded in 1803, according to the John K. Bear Winter Count, at Čhaŋté Wakpá (Heart River). The northern territorial boundary of the Húŋkpapȟa then expanded north from Íŋyaŋwakaǧapi Wakpá.

The Šahíyela were living in a great earthlodge village at the place Where The Hill Stands Alone (Fort Yates, ND), up to 1803, but two things happened: the Battle of Heart River in which their Húŋkpapȟa and Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna allies had expanded their territorial holdings, and the Cheyenne prophet Sweet Medicine’s message to abandon their sedentary life and move west to live and hunt as their Lakȟóta relatives.

The area in the vicinity of the mouth of Íŋyaŋwakaǧapi Wakpá is regarded as a sacred memorial by the Húŋkpapȟa and Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna to a tragedy in 1825. Blue Thunder and No Two Horns recall the year as Mní wičhát’E (Water many-dead), or Dead bodies in the water. High Dog, a Húŋkpapȟa historian, recalls the same year as: Mní wičhat’Á (Water them-died), or Many had died by drowning.

Across the Missouri River and north of the Cannonball Wacipi (Pow-wow) grounds is the site of the deadly drowning incident of 1825.

High Dog’s winter count elaborates further stating They were camping on the bottomlands of the Mníšoše that spring when an unprecedented rise of water quickly drowned over one half of the people. They say that this happened on the east bank of the river, opposite of the mouth of the Cannonball River. The Dakȟóta call this place Étu Pȟá Šuŋg t’Á (Lit. Place Head Horse Dead; Dead Horse Head Point) because, following the flood, the shore was lined with dead horse heads. They had corralled their horses for the night and nearly all were drowned but for a few.

The drowned people and horses were interned in a low rising hill on the spot. This hill was submerged by Lake Oáhe in the 1950s. Locals in Cannonball, ND refer to the south bluff of Íŋyaŋwakaǧapi Wakpá, the west bank of the Mníšoše, the site opposite of Étu Pȟá Šuŋg t’Á, as “The Point.”

In 1840, according to Blue Thunder and No Two Horns, was the year Waáŋataŋ (The Charger) died, there in his last winter camp, along Čhápa Wakpá (Beaver Creek, ND) across the river from the humble community of Cannonball, ND. The Charger received an English captain’s commission in the War of 1812, leading as many as 600 Očhéthi Šakówiŋ (Seven Council Fires; “Sioux”) there at the Battle of Fort Meigs, the Battle of Fort Stephenson, and the Battle of Sandusky. The Charger met dignitaries such as President Martin Van Buren and King George III. He later led the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ under Col. Leavenworth’s command in the Missouri Legion in the first ever US military campaign against Plains Indians in the Arikara War of 1823.

According to the archaeological survey, there was no tribal consultation. Neither out of state firms mention the Arikara village, the Mandan village, Jupiter’s Fort, the 1825 Dead Horse Head Point, nor the 1840 Charger’s last camp. Update: The original image which appeared here might have resulted in the unnecessary destruction of the resource. It was removed at the request of the State Historical Society of North Dakota. Apparently the Dakota Access Pipeline will be installed with spoons, Shawshank Redemption style.

In 2015, two archaeological firms surveyed a corridor for the Dakota Access Pipeline. The corridor plan calls for the pipeline to go through the Arikara, Mandan, Jupiter’s Fort, near or through the 1825 drowning site, and through Capt. Charger’s last camp on Beaver’s Creek. In August of 2016, the Dakota Access Pipeline began to disturb this beautiful confluence of history and culture. Activists have set up camp and have begun to protest the pipeline construction.

Using winter counts, and surviving oral traditions, one can reconstruct the landscape as the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ recall it, with waterways serving as boundaries.

A Lakota world view perspective of Makhoche Waste (The Beautiful Country; The Great Plains). Note: South is at the top of the page.

The Húŋkpapȟa territorial boundaries extended from the mouth of the Čhaŋté Wakpá, west to the Heȟáka Wakpá (Elk River; Yellowstone River) and Čhaȟlí Wakpá (Charcoal River; Powder River), and back east along the Pȟaláni Wakpá (Arikara River; Grand River), then north along the Mníšoše back to Čhaŋté Wakpá.

The Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋ and Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna territorial boundaries extended from the mouth of the Čhaŋté Wakpá, northeast to around Mní Wakȟáŋ (Spirit Lake; Devils Lake), all of Čaŋsáŋsaŋ Wakpá (White Birch River; James River) country, all of Šahiyela Ožú Wakpá (Cheyenne Garden River; Sheyenne River, ND), then south of where the Šahiyela Ožú Wakpá converges with the Mníša Wakpá (Red Water River; Red River of The North), then south towards the Čhaŋ’kasdáta Wakpá (Wood To Paddle Softly River; Big Sioux River), and south again towards the Mníšoše, then back north along the Mníšoše to the mouth of Čhaŋté Wakpá.

Water, especially the Mníšoše, has played an important role in the history of the Lakȟóta and Dakȟóta people. The direction the river flows has shaped the world view of them as well. South is called Itókaǧata, meaning “Facing Downstream.” Western worldview places north as the orienting direction, the opposite holds true for the Lakȟóta and Dakȟóta people.

Water determines boundaries. Water determines life.

By Dakota Wind

Dakota Wind is an enrolled member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. He is a student at North Dakota State University in Fargo, working on a graduate degree in history. Dakota has written for various journals and magazines, and a recent paper of his appears in Karl Skarstein’s “The War With The Sioux,” 2015, for a free e-copy visit The Digital Press. He maintains the history blog The First Scout.