May 1, 2015 - Using the Sacred Language of Emotion to Respond to Social Injustice, By Kyle Hill

I was at an inipi, a sweat, on the Spirit Lake Rez with a good friend whom I consider my brother. Man, it was too hot, piles of rocks! I had to get out (only once, though). After the sweat, in preparation for the ceremony, he was describing the architecture of the sweat lodge as metaphor for our four parts of existence as part of creation. “That first rung, near the bottom”, he said, “It’s easy to grab on to support yourself. This is the physical aspect of our being, and the easiest (but still very challenging) to bring into balance, to obtain. That second rung, this is the mental aspect of our being, which is even more challenging to bring into balance. Next, the third rung is the emotional part of us, it’s hard to reach but I grab onto it during sweat, and pray with it. Last is that fourth ring, at the top, this is the spiritual component of our being. Very few people can obtain balance and gain the ability or achieve balance in this way (spiritual leaders).” Later, still sitting (and lying) outside the sweat, skin steaming, he would tell me that the third rung, our emotional capacity is unchanging, that it cannot be controlled, and for all intents and purposes, a constant. This, he would say, “is our way of communicating with the creator”, a shared language. My friend, I love him for imparting this wisdom on me.

As a psychologist, I have come to understand that six emotions are universal or cross-cultural; anger, disgust, happiness, fear, surprise and sadness. Thus, we can communicate with any human, despite existing language barriers, through these emotions. In many ways, then, our emotions or feelings are often expressed in the absence of any verbal expression. For example, laughing so hard they can’t talk. Grief, for that matter, an overwhelming expression of sadness, that brings us closer, makes us love harder without any semblance of expressive language communicated. Such a beautiful expression of the position of our hearts in relation to our world is nothing less than remarkable and powerful. Most importantly, this language is spiritual, our emotions, when we are lost and need guidance – “listen to your heart”, they say.

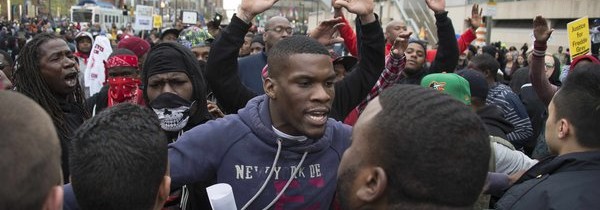

Well, I live in Baltimore, Maryland. I am a guest here, taking a training fellowship before I move back to the Midwest. But I felt something today, April 28, 2015. I felt the city cry, the earth shook for a moment with a language that I’ve never experienced, an expression of collective hopelessness, a language of anger, in the wake of an untimely death of a young Black man. Similarly, we know all too well the collective expressions of sadness and grief when a community experiences a loss of life to suicide. In this instance, however, we saw an uprising polarized by the media, thereby minimizing the historical importance of this collective expression of anger, attempts to communicate the desire to be released from oppression, released from silence, manipulated as destruction by hoodlums and savages. If this sounds familiar, it should. This narrative has reduced and marginalized Indigenous communities, as well as black communities, for centuries. Policies and political tactics predicated on displacement, marginalization and containment have come to defined “America”, for the poor, oppressed, and marginalized communities. Today, not dissimilar to Black Urban America, we see our communities battling in efforts to communicate our language, which is often expressed via externalized and destructive behavior, namely, substance abuse, interpersonal violence, suicide, behavioral problems for children, and high prevalence rates of PTSD (relative to other U.S. races). Though, the point I am trying to make here, is the underlying disorder, the conflict that binds us, is regulation of our right to communicate, a spiritual and universal right that has been undermined through the discourse of Euro-American colonization. Monday, April 27, 2015 a young Black man, Nick Mosby, a Baltimore city councilman dressed in a three piece suit, standing on the crowded streets of Baltimore outside of a recently looted liquor store, would reply to a question by a young Euro-Settler (White) journalist regarding the illegal activity, “When you’re watching this go on, does it break your heart to see this happen?”. Mosby replied, “oh definitely. what it is, is young boys in the community showing decades old of anger, frustration, for a system that’s failed them. This is bigger than Freddie Gray, this is about the social economics of poor urban America…”. This man, along with many others does not condone the illegal activity, but also like many others, see this illegal activity as a “voice”. Whereas, with respect to Native communities, providing a striking similarity with reference to youth suicide and violence as representative as an intergenerational and collective expression of the destruction felt by Euro-American colonization, two notable American Indian mental health researchers write, “Instead of being understood primarily as a private solution to unbearable psychic pain, suicide is rather seen as a public expression of collective pain and is regarded as a predictable (though regrettable) outcome of rampant social disorder initiated by European colonization” (Wexler & Gone, 2012). Admittedly, I am not reducing the value of life in our Indian communities, in any way, to the value of property that was destroyed in Baltimore; although, in either case, what arena or forum provides us the right to express our freedom as sovereign nations/communities and stewards of this earth in an equitable manner?

In closing, and the reason I chose to highlight these efforts of our communities, is that we have reached a time of historical importance where the behavior of creation is responding through expressions of emotion, our language, a sacred language, to the cruelty of injustice. In many instances, we see death as a symbol of rebirth. It hurts, however, to acknowledge the workings of our creator this way, but we feel; A great mystery, indeed. We feel her changing seasons, so as to not be victimized by colonial subjugation, her expression is something we learn to trust, Winter into Spring, sunrise to sunset. Yet, on the other side of the world, she spoke volumes, a 7.8-magnitude earthquake with the epicenter in Gorkha, Nepal, with the death toll passing 5,000, on Tuesday, April 28, 2015 (http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-32494628). We are all related, bound by experiences that terrify us, experiences that hurt us, as well as those that make us come together in celebration. Listen to your heart, make love, pray hard, sing, dance, fight injustice, communicate in faith that our language is a language of the creator. Together, we can reach that fourth rung. “We need one another”, she said, “the greatest of battles are yet to come”.

References:

Wexler, L. M., & Gone, J. P. (2012). Culturally responsive suicide prevention in indigenous communities: Unexamined assumptions and new possibilities. American Journal of Public Health, 102(5), 800-806. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300432 [doi]

Kyle Hill, Ph.D., is a Research Associate at the Center for American Indian Health at Johns Hopkins University.