American Indian Religious Freedom Summit Brings Tribal Leaders to Washington, Efforts to Preserve Peyote Habitat Heat Up

By Darren Thompson

Washington—For the third consecutive year, leaders of the Native American Church of North America (NACNA) gathered in Washington, D.C., to advocate for protections of traditonal American Indian religions and culture. Last week, NACNA planned a two-day summit on Capitol Hill and curated conversations on the state of religious freedom and Indigenous people before meetings with Congressional leaders and their staff.

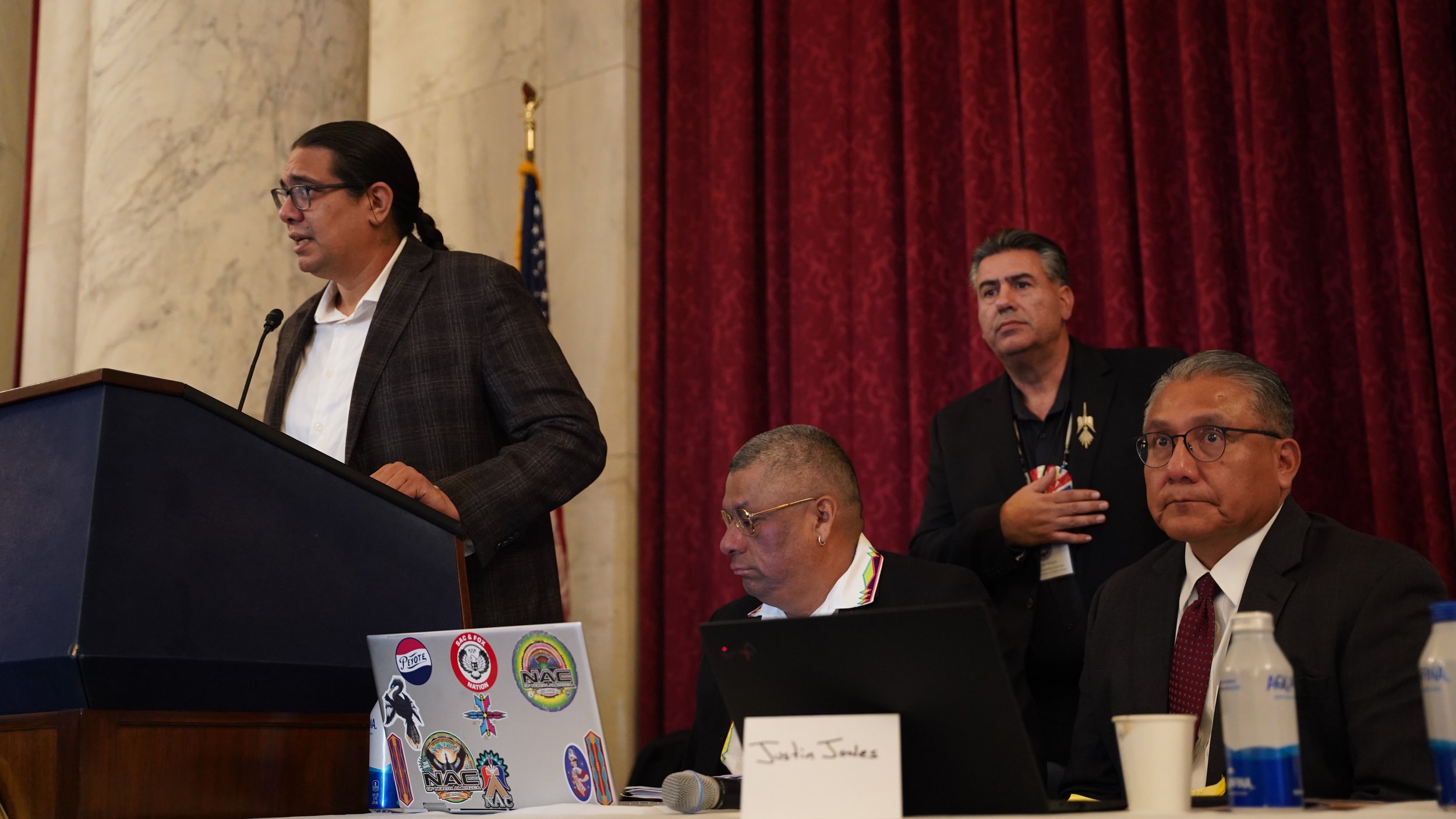

Ceremonial practitioners present their experience in advocating for traditional Indigenous ceremonies in the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs Hearing Room on Monday, November 18, 2024. Photo by Darren Thompson.

“Congress did was Congress was supposed to do,” said Ryan Wilson, an enrolled Oglala Lakota and NACNA’s Director of Congressional Affairs on Monday, Nov. 18 in the Kennedy Caucus Room. "They offered a legislative fix and circumvented a bad Supreme Court decision, then exerted plenary power over Indian Affairs. It’s that spirit is why we come here to this day—we are in grave danger of losing where our medicine grows."

A significant component of the summit acknowledged the 30th anniversary of the passing of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act’s (AIRFA) 1994 Amendment. The Amendment was a result of Smith v. Oregon, where the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that First Amendment does not protect Indian practitioners who use peyote in ceremonies. Then, leaders knew that additional and explicit protections for peyote must be made, leading to AIRFA’s 1994 Amendment. The Amendment explicitly provides legal protections for enrolled members of federally recognized tribes to possess and ingest peyote in traditional religious ceremonies. However, leaders allege that climate change, overharvesting, and widespread use by non-Native peoples has contributed to scarcity of the plant, which leaders say threatens a traditional way of life while violating a federal Indian law.

“Something has happened in the last 45 years, where people are scared to talk about American Indian religions and sacred places,” said Wilson. “This statute—the American Indian Religious Freedom Act—what good is a piece of paper if all of our medicine is gone?”

Peyote is a spineless, slow-growth cactus that grows in its natural state in northern Mexico and in four counties in southern Texas. Its use in Indigenous ceremonies is widespread, in Mexico, the United States and Canada and the history of its use spans thousands of years. The use of peyote in ceremony was predominately done among southwestern tribes, and its growth to many other parts of Indian Country spans back to boarding schools, when many children were first exposed to other Indigneous cultures and ways of life. Today, many of its leaders explain that the use of peyote as a medicine is a connection to the past, to their language and their culture.

“I come here on behalf of my grandchildren, future generations of all of our Indigenous people, trying to make a way to say something on their behalf so that our way of life can continue on in this country," said Darrell Red Cloud, an Oglala Lakota ceremonial leader and descendant of Oglala leader Chief Red Cloud, on Monday, Nov. 18.

Peyote is also a Schedule I drug under the Controlled Substances Act and its possession can lead to a prison sentence, unless you are an enrolled member of a federally recognized tribe. AIRFA’s 1994 Amendment provided specific legislative action to protect a traditional American Indian religion and that practitioners of the Native American Church are permitted possess, ingest peyote in bona fide—“in good faith” in Latin—ceremonies. However, leaders and practitioners voice that there is no true enforcement of this law, which has lead to abuse and interests by non-Native entities to decriminalize mescaline and peyote.

NACNA President Jon “Poncho" Brady addressed the summit on Nov. 18 and phrased that AIRFA has no enforcement and the law is being violated every day. “We all know that [the law is being violated],” he said. “It took all of us in here that come from grassroots teachings and upbringings. We exercise the American Indian Religious Freedom Act and get up every day with the sun and make a prayer or offering.”

NACNA President Jon Brady spoke at the beginning of the American Indian Religious Freedom Summit in Washington, D.C. at the Kennedy Caucus Room in Washington, D.C. Photo by Darren Thompson

“We do all these good things, because that's the way we were taught,” Brady said. Brady, Arikara from the Ft. Berthold Indian Reservation, was elected a second consecutive term as NACNA’s President last June. His focus is continue to advocate for the protection of peyote’s natural habitat in southern Texas so future generations can continue a way of life that has been in his family for generations.

Participants of the two day summit heard from tribal leaders, ceremonial practitioners, leading attorneys specializing in federal Indian law, New Mexico Congressman Gabe Vasquez, Oklahoma Senator Markwayne Mullin, who is also a citizen of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, Native American Boarding School Healing Coaltion (NABS) Chief Executive Officer Deborah Parker, Dr. Ponka-We Victors-Cozad, a former Kansas State Legislator, and Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs Wizipan Little Elk.

Little Elk addressed the summit on Monday and shared some changes that the Department of Interior (DOI) has made in the last adminstration, including revisions to the Native American Graves and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) in 2023. One of the changes Little Elk shared was that NAGPRA must defer to Indigenous knowledge in the repatriation process. “That means we [DOI] have to defer to what Indigneous people say is knowledge and what is the right thing to do,” he said. NAGRPA, passed in 1990, requires museum and federal agencies to obtain consent from descendants, from tribes and Native Hawaiian organiations for any type of communication involving human remains and imposes a 5 year deadline for federal agencies to update all parties involved.

Wizipan Little Elk, Deputy Secretary of Indian Affairs, addressed the American Indian Religious Freedom Summit and highlighted some revisions of the Native American Graves and Repatration Act. Photo by Darren Thompson.

Little Elk also mentioned that President Biden signed into law the STOP Act on December 21, 2022. Known as Safeguard Tribal Objects of Patrimony (STOP), the law aims to prevent the export of human remains, cultural items, and archaeological resources as well as regulate the export of other cultural resources protected under NAGPRA. Little Elk, a Sicangu Lakota from the Rosebud Indian Reservation, has previously met with NACNA to discuss ways to preserve peyote habitat.

The summit’s second day was hosted in the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs Hearing Room and featured panels, awards presentations and a keynote addressed by Suzan Shown Harjo.

“We strongly oppose the decriminalization of peyote at the tribal, state and federal levels,” said Peyote Way of Life Chairperson Frank Dayish on Tuesday, Nov. 19 in the Senate Committee of Indian Affairs Hearing Room. “We embrace the protection of the natural peyote habitat through spiritual and tribal sovereignty. We want government to government relationship and we ask for that today.” Dayish is Diné and the former Navajo Nation Vice President as well as the former NACNA President.

Decriminalization of peyote has been in discussion in several medical communities, but there hasn’t been successful research that the use of peyote is beneficial. Peyote is listed as a controlled substance by the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) and is often recognized as a psychedlic and has also been subject to official decriminalization efforts in California’s legislature, where the bill failed to pass. The National Congress of American Indians passed a resolution in 2021, initiated by its Peyote Task Force, opposing efforts to legalize or decriminalize peyote on local or state levels.

New Mexico Congressman Gabe Vasquez addressed the summit in the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs and said, “It is an honor to join the Native American Church of North America, the National Congress of American Indians, and all of you as we celebrate the 30th anniversity of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act Amendments of 1994.”

“As an advocate, an ally, a member of Congress who values being in unity with Native peoples, I want to use this time to verbally reaffirm my committment to uphold tribal sovereignty, and upholding the rights of Indigneous communities—especially the right to practice and perserve spiritual traditions without inteference,” said Congressman Vasquez. “The 1994 Amendments confirmed what Tribal Nations have always known—that sacred ceremonies are an essential part of culture and identity and community well-being. These Amendments ensures the federal respects and upholds the spiritural heritage of Native peoples."

The summit’s keynote was delivered by Suzan Shown Harjo, Muscogee Creek and Cheyenne and Arapaho woman who’s advocacy for American Indian cultural rights spans back decades, earning her an appointment in former President Jimmy Carter’s adminstration. Harjo was one of many key facilitators that influenced U.S. Congress to pass the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA) of 1978, where Carter also signed AIRFA on August 11, 1978. For her life’s dedication to American Indian people and culture, she was awarded a Presidential Medal of Freedom from former President Barack Obama on November 24, 2014.

Suzan Shown Harjo delivers a keynote address at the American Indian Religious Freedom Summit at the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs Hearing Room on Tuesday, November 19, 2024. Photo by Darren Thompson.

During her keynote, Harjo shared some of her memories throughout her life that have led to historic legislation for Indian Country, including the passing of the National Museum of the American Indian Act of 1989. Harjo said that a convening of ceremonial leaders at Bear Butte in June 1967 brought a decision that led to the creation of the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian 22 years later. “The idea was to create a National Museum of the American Indian, which we called a cultural center, and put it right in the face of the Capitol so that the people inside the Capitol would have to look us in the face whenver they made laws about us,” Harjo said. “So, that was a big deal and that came true. It only took 22 years and now you see the National Museum of the American Indian and faces the Capitol.”

Harjo also shared her insight to getting legislation passed, and that the broader the issue that can be explained the better it will work for people. “If a law is narrow and constrained, where a lot of pieces of legislation are, then people won’t fit in the law," Harjo said. In her reflections, she shared the many conversations and issues her generation has stood to protect including protections of sacred objects and the sacred sacrament of peyote. “How do we tie all of this together?” Harjo questioned. She then said that the American Indian Religious Freedom Act was a direct answer to all of those questions in 1978. “We made that door very broad, and we always thought of it as a policy door, not as regulations,” she said. “That down the line, more rules or regulations can be added or further discussed.”

“First, you have to declare that it’s a U.S. policy to preserve and protect religions—that has to be the first thing—and why?” Harjo questioned. “Because for 50 years, from the 1880s to the 1930s, there was the civilzation regulations that governed all federal activities and that’s where you have all Native everything, or everything that was distinguished as Native, was criminalized under the civilization regulations."

After Harjo's presentation the Native American Church of North America President Poncho Brady and his wife Rebecca “Tookie" Bray gifted Harjo a star quilt along with a cedar box and golden eagle feather. She was smudged with sweet grass by Ryan Wilson and Darrell Red Cloud gifted her a golden eagle feather after he led a prayer to the four cardinal directions.

Darrell Red Cloud (left), Oglala Lakota, delivered a prayer in the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs Hearing Room for Suzan Harjo (sitting) with the help of Ryan Wilson (right). Photo by Darren Thompson.

Other panels included tribal leaders including Navajo Nation Vice President Richelle Montoya, Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma Governor Reggie Wassana, and an appearance by Oklahoma Senator Markwayne Mullin.

On Wednesday, November 20, participants separated and met with various Congressional staff members to discuss their hopes in gaining support from Congress, where they are asking for $5 million for a “Peyote Habitat Conservation Initiative Demonstration Project” either adminstrated by the U.S. Department of Agriculture or the U.S. Department of Interior. Their hopes is that funding appropriated will compensate private land owners in Texas, where peyote grows in its natural habitat, to convert their lands to conserve and protect peyote.

However, another barrier is the free establishment clause. “Traditional American Indian religions have already been established under federal Indian law,” said Greg Smith, a 34-year-veteran attorney at Hobbs & Straus at the American Indian Religious Freedom Summit on Monday, Nov. 18. “Next is protecting an endangered and vital plant that is central to an established American Indian religion.”